Dance: Two Dramatically Different Views of Dance from the Early Twentieth Century.

By Francine L. Trevens

ART TIMES September/ October 2012

|

Freud claimed there are no coincidences. Therefore, I guess I must attribute to kismet the fact that two widely divergent books about dance during the early-to-mid twentieth century landed on my desk at the same time.

First to arrive was Rock ’n’ Roll Dances of the 1950s, by Lisa Jo Sagolla, part of the American Dance Floor series from Greenwood.

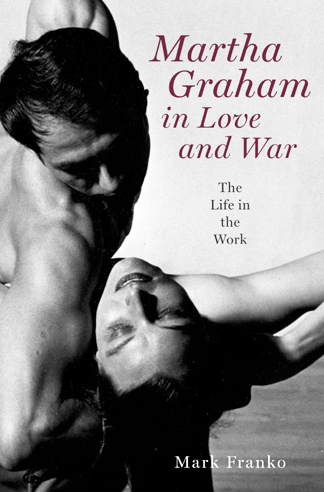

Second was Mark Franko’s titled Martha Graham in Love and War subtitle The Life in the Work from Oxford University Press.

Both are profusely illustrated hardcover books. Both are 6 ½ by 9 ½ inches. Both are histories of dance during that period. Both are under 200 pages with extensive glossaries of notes and bibliographic attributions.

There all similarities end. To use a culinary comparison, one is hot dogs, the other sweetbreads. I’d guess over 90% of people enjoy hot dogs. I’d guess less than 1% enjoy sweetbreads.

Any one with interest in Rock ‘n’ Roll history can enjoy reading Ms Sagolla’s book, available in both hard cover and as an ebook. For those of us who were around during that period it is a big helping of nostalgia. I was particularly impressed at the number of dances which were inspired by Rock ‘n’ Roll music – dances I never knew existed although I was a teenager in that period. Some of those she details, many of which had their beginnings in African-American dance are The Hard Line and The Madison, The Stroll, The Slop, The Walk, The Circle Dance and then, the major change in 1960 - The Twist..

Ms. Sagolla, a columnist and critic for Backstage and the Kansas City Star, teaches at Columbia University. She has authored several other books and choreographed over 75 productions. Her style presents a crisp, clear and concise history of the musical phenomena, which dramatically altered social dancing.

The photos in this book have the same spontaneous feel as the dancers themselves had back in the day. The music was such, as Ms Sagolla points out, that young people could not merely listen, even if in a theater. They had to move to the beat. They danced on their seats and in the aisles.

A good deal of space is given to the first reality TV show – American Bandstand - which in turn gave rise to many of the new dances. It discusses not only the moves of Elvis Presley, which so scandalized the older generations, but the fact that most musicians playing this new music also were impelled to move to it.

She notes societal, economic and political causes and fallout. She remarks on the emergence of the adolescent culture in the 50s period of economic abundance. She includes the beginning of dancing with a partner without making physical contact. While I jitterbugged to this music, I settled down to marriage and motherhood before moving on to that phase. This twist solo dancing reminded me, when I first saw it, of whirling dervishes. It seemed dance had moved from a courtship ritual back to its prehistoric beginnings as a mystical set of moves. It preceded and perhaps predicted the “me generation”!

Ms. Sagolla devotes a good deal of space to 50’s films which helped keep Rock ‘n’ Roll alive and active. It is a comprehensive and easily comprehended history of the early twentieth century dance craze which reflected the American spirit of the time. She shows how these dances began with teenagers and worked their way into older generations.

Mr. Franko, who authored many books and won the 2011 Outstanding Scholarly Research in Dance Award from the Congress on Research in Dance, is Professor of Dance at the University of California, Santa Cruz; Director of the Center for Visual and Performance Studies, and editor of Dance Research Journal.

He does more than research, he excavates into the psyche of Ms Graham and presents how during and following her time with Erick Hawkins, various dances came into being.

Unlike Ms. Sagolla’s, Mr. Franko’s book was not intended for the average reader. It is a deep and dense delving into the psychological, mythical, social, political and environmental influences which moved Martha Graham from the late 30’s through the early 50’s. He examines, expands and explains multiple causes and especially the affect of Erick Hawkins on her private life and her creative work in that time period. Mr. Franko favors an elitist vocabulary which will have college students sitting with a dictionary at their elbow to be sure they get all the nuances of this intense scholarly work.

Jacket design Caroline McDonnell – Jacket design Caroline McDonnell – cover photo by Barbara Morgan |

When I began reading this book, I remembered an incident in my own career. I had just moved to Springfield, Massachusetts and was hired to write performance reviews for the weekly newspaper. I was on my way to tea at a neighbor’s when the paper with my first review arrived. I grabbed it and brought it along. My hostess invited me to read the review aloud, which eagerly I did. She complimented me.

Her husband, who had been in the adjacent room, came in and disagreed. He asked me for whom I thought I was writing this review. The New York Times? Harper’s? He pointed out that my readers were just average local people not the intelligentsia and I ought not to try to show off by using all the longest words I could find.

I had not tried to impress anyone - I had written the review using what I considered my reading and writing vocabulary. That experience taught me you must write for your reader. Mr. Franko’s reader is a very well educated, committed and learned one. That is the audience for this book.

To support his conclusions, he refers to Ms Graham’s correspondence, notebooks, and the remarks of those who worked with her at that time. His endnotes, bibliography and index run to over 150 pages.

It was interesting to contrast the highly intellectual appeal of Graham’s work to the elitist middle aged and older audience, which later came to appeal to the younger audience, the reverse of rock ‘n’ roll which appealed first to the younger audience and then the older generations!

Martha Graham in Love and War is a fascinating dissection of how her relationship with Hawkins affected her work and her persona. Franko notes the “intense creative activity linked to her relationship with Erick Hawkins.” The many artistic photographs by Barbara Morgan dramatically capture much of that work.

Graham’s earlier works were pro democracy and anti Fascist. After she began to choreograph roles for both men and women she moved deeply into myth. Franko explains the influences which led her there.

Hawkins was a guest artist in 1938 – the first male dancer Martha Graham and Dance Company employed. He appeared in her American Document, which included spoken word and in which Graham and Hawkins danced their first duet. Jean Erdman joined the company in that piece. Hawkins was fascinated by myth, and Graham through his influence and through Erdman’s husband, Joseph Campbell, became immersed in myth as well.

In 1942, after Hawkins joined the company, Graham presented a program designed to showcase him. Despite her being fifteen years his senior, and having choreographed over a dozen dances prior to American Document, she had her own dance company and a loyal following. It was not easy for the ambitious young man to find himself romantically involved with her. There had to have been problems over the male-female dynamic so prevalent at the time.

First duet for Martha Graham and Erick Hawkins in Graham’s American Document (1938) Courtesy of the Music Division, Library of Congress First duet for Martha Graham and Erick Hawkins in Graham’s American Document (1938) Courtesy of the Music Division, Library of Congress |

Hawkins was more than a romantic interest and a talented dancer. He became a driving force in the growth of her company as he soon became the fundraiser for the company as well as advisor, accountant, producer, technical assistant and company manager. The two married in 1948.

Hawkins also moved her company forward by raising sufficient funds so that instead of merely a piano she was able to have nine instruments play the music for Appalachian Spring which had both Hawkins and Merce Cunningham as dancers. It put Graham on the world map of great dancer/ choreographers. It was followed by many dance pieces based on various myths with her unique viewpoint and psychological undertones. She used other male dancers and in 1944, at war’s end, introduced Yuriko, a Japanese-American dancer into the troupe, breaking the racial barriers then prevalent. Yuriko subsequently reconstructed many of Graham’s dances.

Hawkins left the troupe in 1951. They divorced in 1954. The great dancer/choreographer turned to a psychiatrist to help her cope. She also turned to drink.

Franko is far more sympathetic to Hawkins than were most writers of that day. He explains the deep emotional reactions of Ms Graham to Hawkins departure and how the dances which followed their split were related to that change in her life. He goes into such delectable details about her dance piece called Voyage, in its several versions, that its loss is made poignant. It was dropped from the repertoire because critics and audiences did not want the Martha Graham who was attempting to find herself. They forced her to return to myths.

Franko details the conception, creation and multi levels of American Document, Appalachian Spring, as well as Night Journey, Punch and the Judy, Dark Meadow, Cave of the Heart, Errand into the Maze, Death and Entrances, Gospel of Eve, Clytemnestra and more.

For a deeply moving and informative view of Ms Graham and her many achievements during those years, nothing can be more informative and fulfilling than this elegant volume.